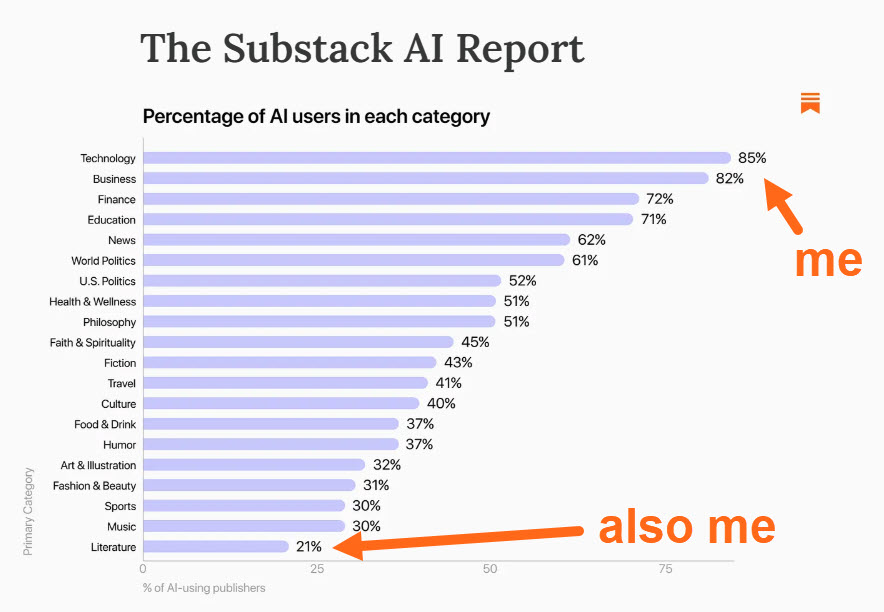

AI is making these author scams more pernicious

Because they crave attention for the books they’ve worked years on, authors are perpetual targets of scams—and AI is making author scams all the more dangerous. In recent months, I’ve encountered many of the most common ones, including these four types.

1. Book promotion services scams

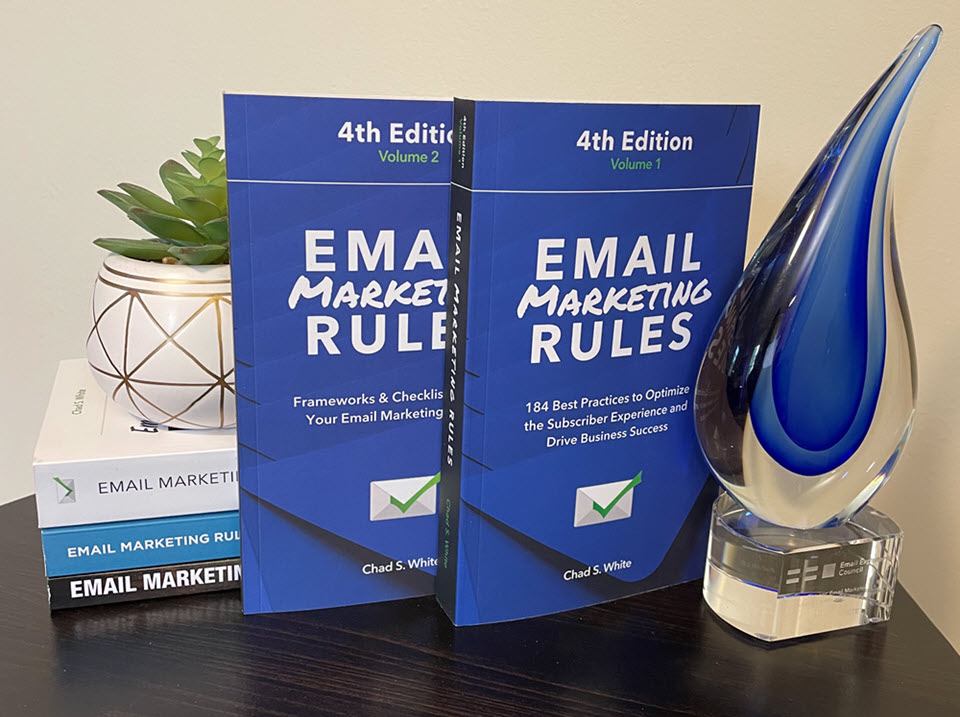

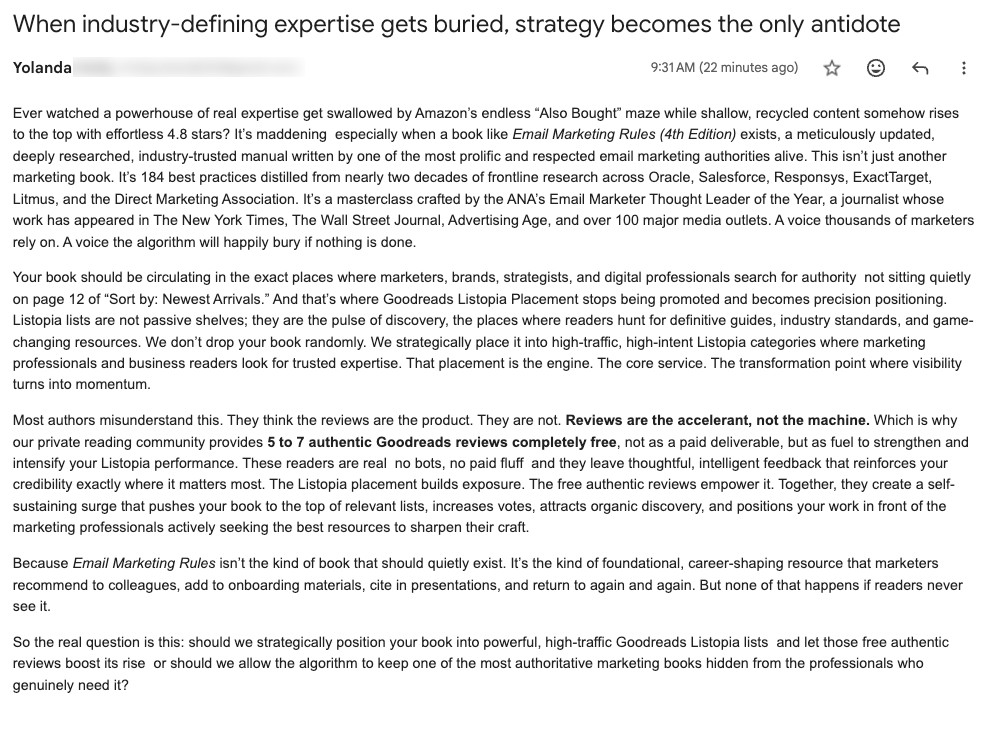

These prey on authors’ fears that their book is being overlooked. Here’s an email I received about my nonfiction book, Email Marketing Rules. The opening paragraph uses AI-generated text that pulls from my book description and bio (probably from Amazon).

2. Book review scams

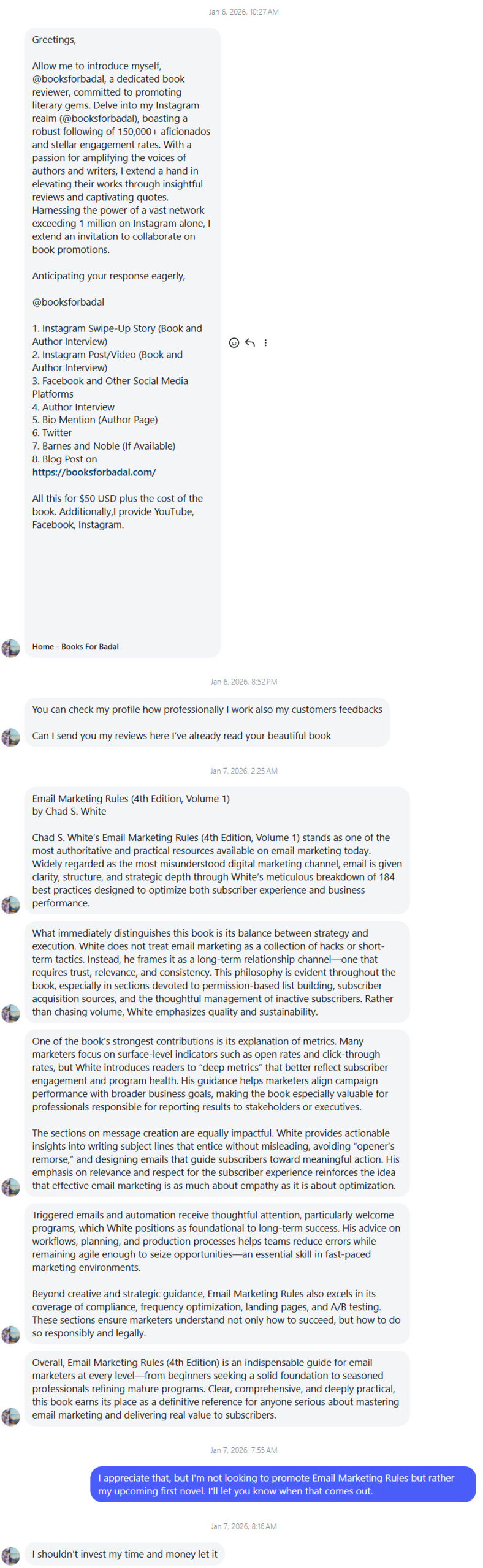

Every author wants more book reviews, whether they’re on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, or Goodreads, or by an influencer on social media. I recently followed back a book reviewer on Instagram and was immediately DMed about book review opportunities and cost. That’s fine and, honestly, expected. But then the reviewer claimed they’d already read my book and asked if they could send me a review to look over. And without me responding, they sent me a lengthy review the next day.

Now, the review is spot on. I don’t take any issue with that. But I’m not so full of myself to think this person had actually read my book already. And if they had by chance, no one would proactively invest time in writing a review before knowing if they have a paying customer. But spending a minute to write an AI prompt? Sure. You might proactively do that.

As much as I want more reviews and social media mentions, I want them by real live people who read my books and enjoyed them.

3. Book club scams

These scams have been a frequent topic of conversation in The Authors Guild forums, which are a great resource for new and veteran authors. I received this email purportedly from Kate at UK Book Club. Now, UK Book Club is real, and one of the moderators is indeed named Kate.

However, you might notice some odd things about this email. For instance, the email address is a Gmail address. That’s a common red flag. But also, the Gmail username is katemoderatoor with two O’s. A strange choice. The email itself is full of punctuation errors, including missing commas, apostrophes, hyphens, and a question mark on the closing and crucial sentence.

Oh … and the subject line appears to include an AI prompt with instructions to not use any dashes—you know—because em-dashes are a sign of AI usage. The irony.

4. Outreach from fake author accounts

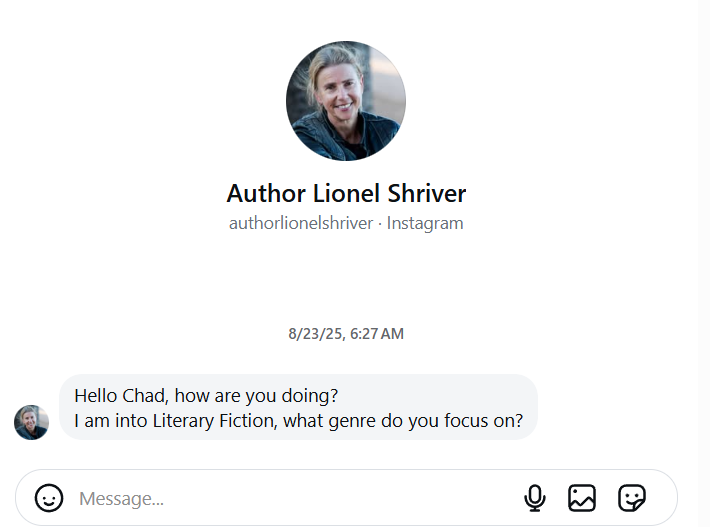

These accounts follow you and then, if you follow them back, build up a rapport via DMs. Only later do they encourage you to use scam promotion services, scam representation, or something else, which are often pitched as the secret to their success.

I was approached by a fake Lionel Shriver. I’ll confess I’d never heard of her, and her follower counts were similar to mine. But when I followed her back, she quickly DMed me, asking me a question that was readily answered by my profile. So, I did a little research, recognized it as an impersonator account, and unfollowed the account. Apparently, Instagram has also recognized that it’s an impersonator account, because it’s been removed.

While AI didn’t play a noticeable role in my interaction with the account, I’ve heard of cases where AI auto-replies if you respond to the initial outreach. If you’re uncertain, try replying in a foreign language. An AI won’t miss a beat and will respond like nothing unusual has happened.

Of course, there are many more forms of author scams, including fake offers of representation. The January/February 2026 Writers Digest magazine had a doozy of a scam, where a Big Five publisher offered to publish your book. All you had to do is sign on with a particular favored agent … which charged a client fee.

Other times, it’s not an outright scam. Instead, you’ll pay for something that should be free or pay way too much for the little you receive, such as entry fee for an award with zero clout.

In the years ahead, AI tools will make it easier for scammers to target authors and harder for authors to quickly recognize the danger. If you’re not already, be suspicious of everything—especially anything that has the slightest whiff of being too good to be true.

Additional resources about author scams:

The Authors Guild: Publishing Scam Alerts

Reedsy: Book Publishers to Avoid: 5 Types of Shady Companies

To receive future posts for free or to become a Patron and support my dystopian sci-fi novel and get special thank-you goodies upon its publication…