The Age of De-Skilling: Who do you want to be?

From the gramophone to compass to the computer, advancements in technology routinely cause people to abandon skills, says The Atlantic’s Kwame Anthony Appiah in The Age of De-Skilling (link to gift article).

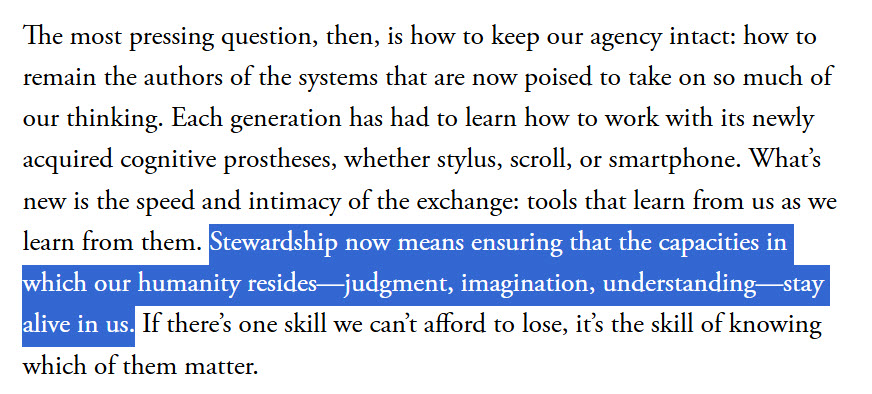

“It’s a reassuring pattern—something let go, something else acquired,” he says. “But some gains come with deeper costs. They unsettle not only what people can do but also who they feel themselves to be.”

Of course, AI is the next big advancement that’s causing the current cycle of de-skilling. The question is: What skills will people be giving up? And how will that impact their identity?

In these cycles, people have several paths available to them:

1. The cyborg

They can use the technology collaboratively, keeping their skills while gaining speed, precision, or other benefits from the technology.

2. The monitor

They watch over the technology as it does their former job, stepping in to assist when the technology falters. In this role, the person invariably loses skill and their former identity.

It’s around these two choices that most of the conversation about AI has revolved. Will you be the “human in the loop” that stays actively engaged in your craft? Or will you be the “human on the loop” that merely oversees and signs off on the work the technology does?

But I think there are two other options.

3. The innovator

Freed from some aspects of their profession or task, they specialize in one or more of the remaining aspects. In the age of AI, this means focusing on very niche subject areas where there’s relatively little domain knowledge—or, more commonly, being on the forefront of new discoveries. The innovator doesn’t compete with the new technology. Instead, they expand knowledge or pioneer new methods, which over time improve the new technology or fuel the next technology innovation.

4. The artisan

Some people will continue doing things the old way. They will maintain their skills and identity, but compete directly with the new technology. In some cases, a critical mass of consumers will appreciate this human- or hand-crafted product or service, making it a viable choice. In other cases, there won’t be a viable market.

I recognize that not every person in every instance will have full discretion over which of these paths they take as AI spreads across industries. However, in my day job, I’m going to lean into being a cyborg and specialist, as that makes me the most valuable as a digital marketer. And in my night job as a novelist, I’m going to lean into being an artisan, as that best aligns with my values as a novelist.

Related posts:

Where to draw the line with genAI

To receive future posts for free or to become a Patron and support my dystopian sci-fi novel and get special thank-you goodies upon its publication…